Here’s this month’s poetry post from our friend, poet and translator, Keiji Minato.

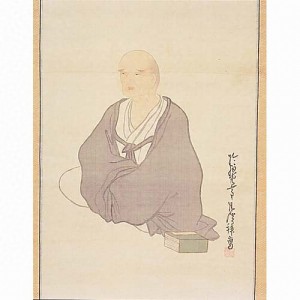

My first article for Deep Kyoto took up the topic of YOSA Buson‘s (1716-1784) hokku (or haiku). As it says, and you all probably know, Buson was a great haiku master and painter, and I would like to add here that he was also an experimental poet who tried poetic styles that had never been used in the history of Japanese literature. His three longer poems show great results: “Hokuju-rosen o Itamu†(北寿è€ä»™ã‚’ã„ãŸã‚€), “Shumpu Batei Kyoku†(æ˜¥é¢¨é¦¬å ¤æ›²; Song of the Spring Wind on the Horse Bank), “Denga-ka Sanshu (or just Dengaka)†(澱河æŒä¸‰é¦–; Three Poems on Yodo River), all published in Yahanraku (夜åŠæ¥½; Midnight Music; 1777). The topic this time is “Dengaka.â€

澱河æŒä¸‰é¦–    与è¬è•ªæ‘

Denga-ka Sanshu (Three Songs on Yodo River)  by YOSA Buson

春水浮梅花 å—æµèŸåˆæ¾±

錦纜å›å‹¿è§£ã€€æ€¥ç€¬èˆŸå¦‚é›»

The spring water floats down plum blossoms

toward the south to join Yodo River

Do not loose the gilt-threaded mooring lines

On the rapids a boat runs like a lightning

èŸæ°´åˆæ¾±æ°´ã€€äº¤æµå¦‚一身

船ä¸é¡˜åŒå¯ã€€é•·ç‚ºæµªèŠ±äºº

Once Uji River joins Yodo River

their mixing flows are like one body

On the boat hopefully we will sleep together

and be living in Naniwa forever

å›ã¯æ°´ä¸Šã®æ¢…ã®ã”ã¨ã—花水ã«

æµ®ã¦åŽ»ã“ã¨æ€¥ã‚«ä¹Ÿ

妾ã¯æ±Ÿé ã®æŸ³ã®ã”ã¨ã—影水ã«

沈ã¦ã—ãŸãŒãµã“ã¨ã‚ãŸã¯ãš

You are like a plum blossom dropped

on the water that floats away so quickly

I am like a willow tree whose shadow

is sunk too deep in the water to follow

“Shumpu Batei Kyoku†is a kind of collage in which Chinese-style verses, freer Japanese lines based on Chinese styles, and hokku-like 575 lines. In “Denga-ka,†he tries a similar style but in a smaller scale. The first two stanzas are written in a major Chinese style, Gogon-zekku (五言絶å¥), which has four phrases, each of which has five letters. The last stanza flows more freely, yet still based on Chinese writing styles.

What is appealing about the poem, however, lies more in content than in form, or in the intersection between content and form. The narrator is a female who sings of her affair with a man. The described geography shows that the relationship is between a merchant from Naniwa. a city of commerce, and a yujo (éŠå¥³; performer-prostitute) in Fushimi, a town in the south of Kyoto City. The poem superimposes them with the two rivers, Yodo (澱水) and Uji (èŸæ°´) (On today’s map Uji and Katsura Rivers join around Yahata to be Yodo River; See Google Map!). The image of the joining rivers of course has sexual connotations, which are strengthened by “the gilt-threaded mooring lines†in the second line, which connotes an obi (a broad sash tied over a kimono) the yujo is wearing.

Please note that the poem cannot be read in one sequence. In Stanza Two, as the two rivers merge and flow toward Naniwa, the lovers will happily live together ever after, at least in the yujo’s hope. In Stanza Three, however, the tone is totally different (which is emphasized with the difference of the styles). The yujo has no illusion about their future: their affair will no doubt be short, and the man will never come back. Stanza One and Two might be a speech the yujo makes to her lover, and Stanza Three sounds more like her inner voice which cannot deny the bleak reality. So, in my reading the poem diverges from Stanza One in two different directions: Stanza Two (dream) and Stanza Three (reality), between which the yujo’s mind is torn apart. It is interesting that the reading of the poem simulates the form of the rivers.

As I re-read the poem, lines from Gillaume Apollinaire’s “Le pont Mirabeau†came to my mind:

L’amour s’en va comme cette eau courante

L’amour s’en va

Comme la vie est lente

Et comme l’Espérance est violente

Vienne la nuit sonne l’heure

Les jours s’en vont je demeure

**********************************

This text and translations by Keiji Minato. Keiji writes a guest blog for Deep Kyoto once a month introducing Kyoto’s poets and poetry. You can find former articles by Keiji Minato here.