Ian Ropke writes…

Ikkyū was a Zen monk who was famous for burning the candle of life at both ends. By day, he was devout and extremely accomplished monk and scholar. By night, he reveled in the so-called “floating world†of drink and women. He lived in tumultuous 15th century Japan at a time when most of the country was ruined by civil war.

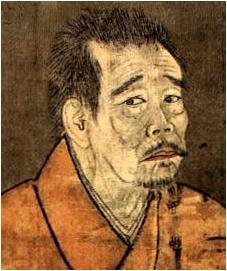

Ikkyū was born the illegitimate son of an emperor and a court lady. As a boy he already displayed remarkable abilities and intelligence. He was particularly attracted to Chinese culture which he absorbed and used for the rest of his life in his poetic imagery. He was not good looking. His Zen apprenticeship began at age 13 at Kennin-ji Temple, Kyoto’s oldest Zen temple, located, ironically, just south of the first-class world of wine and women: Gion. From a young age, he took naturally to criticizing the world of hypocrisy he saw around him in temples and in the ruling families of his day.

His first spiritual master, Keno, lived in an old rundown temple on Lake Biwa, Japan’s largest lake (in Shiga Prefecture, just east of Kyoto). He spent much of his life on the shores of the lake. When Keno died, he moved in the Daitoku-ji branch temple headed by the monk Kaso. To support the temple, which also had little money, he crafted dolls which he sold in Kyoto. From this time onwards he also began to spend much of his free time in the local taverns, brothels and fishing huts.

He achieved enlightenment while listening to a band of blind singers performing a tragic love ballad on the shores of the lake. From that time, he took the name Ikkyū, which literally translated means One Pause. He wrote this poem just after reaching enlightenment the first time.

From the world of passions,

returning to the world of passions.

There is a moment’s pause —

if it rains, let it rain,

If the wind blows let it blow.

Apparently in the summer of 1424, he experienced enlightenment a second time while meditating in a fishing boat when he heard the call of lone crow at twilight. His master issued him a certificate of enlightment the second time and this caused Ikkyū to storm out of the temple in disgust. Nevertheless, Kaso hoped to make Ikkyū his heir when he died. Ikkyu cared for him in his dying days, going as far as to clean the old man’s excrement with nothing but his hands. Another monk was given the position of heir and Ikkyū began a long period of wandering. He wandered around for 30 years until he was nearly 60. During this time, he saw himself as a crazy cloud and increasingly identified with the philosophy of the monk Rinzai, founder of the Rinzai sect of Zen Buddhism and Daito (founder of the Daitoku-ji monastery Ikkyū would one day be the head abbot of). He married and had a son, who went on to become of the Japan’s most respected tea masters. Indeed, Daitoku-ji Temple is closely connected with the Japanese tea ceremony even today.

Like Rinzai he had long hair and beard. However, unlike Rinzai and much of the monk and samurai establishment, Ikkyū rejected the traditional life of the men of his day. He took female students and considered them his equal. He also drank wine, ate animal flesh and had many female lovers. In his late years, he became a prominent practitioner and patron of the arts, including calligraphy, painting, poetry, which he practiced as a way to transmit Zen.

In 1474, when Ikkyū was in his late seventies and had a 30-year-old blind composer musician mistress, the emperor ordered him to become the head abbot of prestigious Daitoku-ji Temple. The temple had nearly been destroyed by the Onin Wars that raged across Kyoto for more than 15 years. It was a tough task, but he succeeded. Seven years later, the temple had nearly been restored and Ikkyu died.

Natural, reckless, correct skill;

Yesterday’s clarity is today’s stupidity

The universe has dark and light, entrust oneself to change

One time, shade the eyes and gaze afar at the road of heaven.

Text by Ian Ropke. Ian Ropke is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Osaka and Kyoto and director of Your Japan Private Tours. You can read his previous articles for Deep Kyoto here.

Learn more:

The following links are affiliate links. The owner of this site may earn a commision from qualifying purchases.

“The poems in this collection express the unborn bliss of Ikkyū’s realization and equally his devastation at the horrors of this world. They are peopled with ancient Chinese poets, cantankerous Japanese Zen Masters, contemporary warlords, and his lover Mori, a blind musician who lived with IkkyÅ« the last eleven years of his life. All of this is his Buddhism. His awakening outshines the small idols of reason, emotion, self, desire, doctrine, even of Buddhism itself.”Buy on Amazon Buy on Amazon.co.jp |

|

this ink painting of wind blowing through pines – Ikkyū’s work is translated here by poet Stephen Berg. |

“In this volume, acclaimed poet Stephen Berg presents freely adapted “versions†of many of Ikkyu ’s most compelling poems as well as new poems inspired by Ikkyu.” “Ikkyu, the Zen master who scoffed at Zen is one of the world’s grand pessimists…on the other hand, when he writes about sex his earthly reckless enthusiasm is unmistakable. Stephen Berg’s adaptations are just right for Ikkyu ’s bitter sensitivity. From them one gets a very complex, even self-contradictory enjoyment, which is the mark, “Ikkyu scandalized the Zen community of his day and is likely to scandalize some readers even now – his short poems are simultaneously bawdy, abrupt, vulgar and reverential…It is impossible not to love the velocity and variety of his verse.†—Philadelphia Inquirer |

Arntzen’s classic study and select translation of the Japanese medieval Zen poetry Crazy Cloud Anthology (KyÅunshÅ« 狂雲集) by the Buddhist monk IkkyÅ«.”Translations from the Crazy Cloud Anthology, or KyÅunshÅ« 狂雲集, IkkyÅ«’s major collection of poetry in literary Chinese, form the core of this work. IkkyÅ«’s biography and historical context of medieval Japan are outlined in the first part of the introduction. The analysis sections provide a portal for the reader to enter the world of the poems by demonstrating how IkkyÅ«’s poetry produces experiences of Zen most often through the dialectical use of allusion.” |

“This book tells the life stories of Ikkyu, Hakuin, and Ryokan. Each was an outstanding figure who manifested Zen in his own way. Ikkyu was unconventional and uncompromising, a relentless enemy of the hypocrisy that pervaded the religious circles of his day. Hakuin underÂwent a strenuous apprenticeship to become a Master Teacher of Zen, training hundreds of disciples and insisting that they endure the same trials that he had. Ryokan, in contrast, was a gentle recluse who lived in quiet hermitages, savorÂing nature and writing poetry. All three were artists who employied brush, ink, and paper as a means of transmitting Zen teachings and creating unique works of art.”Buy on Amazon Buy on Amazon.co.jp |