This article contains affiliate links. The owner of this website may earn a commission from qualifying purchases.

Performances for the Gods

Ian Ropke writes…

Japanese Noh theatre is one of the oldest dramatic forms in world. The early developments of Noh lie in the festive entertainment of various kinds (dance, simple plays) performed at temples and shrines in the 12th and 13th centuries. Noh drama for much of its history was favored by the samurai, priest and aristocratic classes. Unlike Western theatre, the Noh performer is more a storyteller who suggests the meaning of the play with his movements and through his appearance or costume. Until 100 years ago, the audience was intimately familiar with the plot and the historical or mythological background of the play and knew how to interpret and appreciate symbolic and indirect references to Japanese history, much like early audiences at Shakespeare’s plays.

Nearly all of the Noh plays performed today were written by the start of the 17th century. The vast majority of the core Noh repertoire were written by Kan’ami Kiyotsugu (1333-84) and his son, Zeami Motokiyo (136-1443) in Kyoto. Zeami, as the father of Noh, developed most of the principles upon which Noh theatre has always been based. Today, of the roughly 2,000 Noh texts that are known to exist, only 230 core works are still performed regularly. Today, the Noh world has two centers: Kyoto and Tokyo.

Dramatically, the Noh theatre is by no means as complicated as Western theatre forms. Essentially, there is no plot and everything on stage takes place very slowly. The plays are quite short: not much more an hour, during which only two or three hundred lines will be chanted. The plays are usually tragic and related to themes beyond the human realm in a space populated by gods, demons and ghosts. The setting is generally a very simple place that has some special significance to the main character or actor (shite). The other main performers on the stage are the waki (playing the role of a Budhdhist priest or the opposite role of the shite) and the one or two actors that “assist†the shite and waki. All the performers in a Noh play are men, even when the role is female.

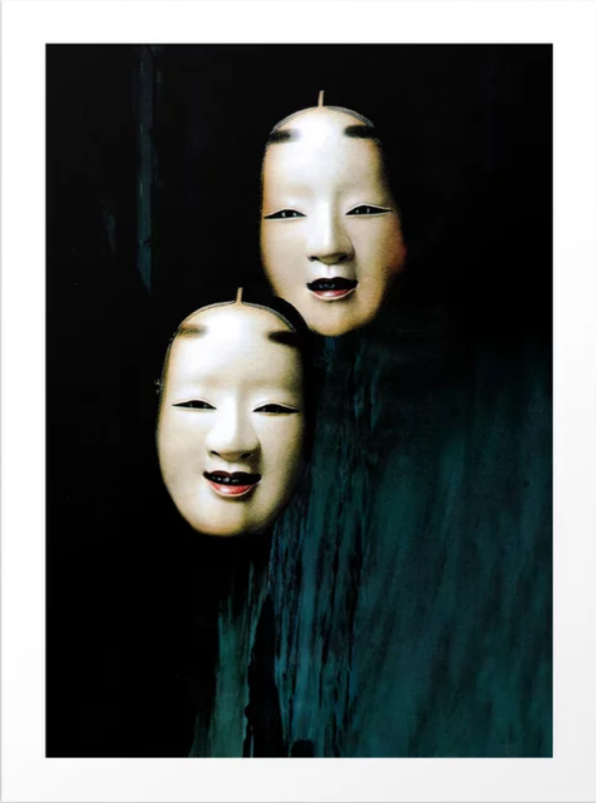

In addition to the main actors on the stage, who often wear symbolic wooden masks and carry one of two simple props — a fan or a wooden staff — Noh performances involve a chorus of 8 singers and up to four musicians playing one of two kinds of instruments (3 sizes of drums and a flute). The rhythm of the drums indicated the degree of tension the main actor is trying to convey to the audience. All the elements blend into a single harmonic whole and no one single element dominates. In ancient times, when a theatre event could last most of the day, comic relief kyogen plays were often performed between each Noh play. Today, kyogen exists as a theatre form that is usually separate from Noh, though exceptions like the annual Takagi Noh (Fire-light Noh) in June have continued.

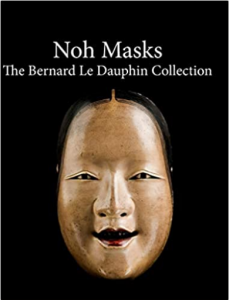

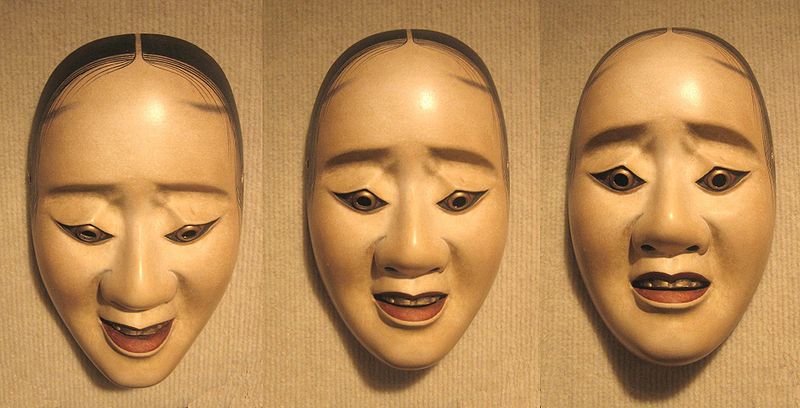

The moving spectacle of the Noh is inseparable from the striking, often haunting beauty of Noh men (masks), which can be divided into five basic categories: shin (gods), nan (men), jo (women), kyou (crazy entities) and ki (demons). There are about 80 distinct masks. It takes a master mask maker about one month to finish a single mask.

Though many Noh masks appear to be expressionless, they actually function to express any of the wide range of human emotions – joy, anger, sorrow or pleasure – common to Japanese dramas. Worn with a downward tilt, the mask is said to express sorrow. Tilted upward, the mask conversely is interpreted to express joy and laughter. A Noh mask contains the very soul of the character it depicts. When an actor begins to prepare for a role, it is to the mask that he or she looks to discover the essence of the character. Until the mask is in place, the actor is simply himself, but once it is on, he is transformed — body and soul — into that character. Given the central importance of the mask to Noh, it is no surprise that every Noh school treats its masks with a profound reverence. The leading schools often use masks in their performances that are hundreds of years old!

Kyoto has two major Noh performance groups: Kanze (descended from Zeami) and the Kongo troupe. Plays are held regularly and are not expensive. Try and experience the wonders of this dramatic form at least once: you won’t be disappointed.

Text by Ian Ropke. Ian Ropke is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Osaka and Kyoto and director of Your Japan Private Tours. You can read his previous articles for Deep Kyoto here.

Learn More:

See also: Takigi Noh (Noh by Firelight)

the能.com probably has pretty much everything you need to get started with Noh drama…