Tourists who came from afar were apt to think that the Gion Festival consisted of only the parade of floats on the seventeenth of July. Many also came to Hiezan on the night of the sixteenth. But the real ceremonies of Gion Festival continued all through July. In the various districts in Kyoto, each of which had its own Gion float, the festival bands began to perform and the amulet rituals commenced on the first of July…

Yasunari Kawabata, The Old Capital,1962, Tuttle Publishing.

Last night Mewby and I wandered through the festival crowds, down Shijo towards the warren of streets that lie west of Karasuma. One of the main pleasures of the festival is simply wandering about and watching all the people promenading in their summer finery. Mewby, herself looked lovely last night in her purple yukata.

The story of the Gion Festival goes back to Heian times during a time of plague. The Emperor of the time ordered special prayers to be said at Yasaka Shrine and halberds were set up in the city as protective amulets against the evil of the disease. Over time this ritual was repeated and the halberds became increasingly stylized and elaborate, eventually transforming into the festival floats or hoko, we see today…

Another pleasure of the festival is viewing the floats. There are two kinds: yama and hoko. The hoko (the modern day descendants of the Heian era ritual halberds) will be hauled to Yasaka Shrine on the 17th in the grand parade known as Yamaboko Junko. They contain many fine art treasures and tapestries, reflective of the city’s rich mercantile history. John Dougill writes in his marvellous book Kyoto: A Cultural History

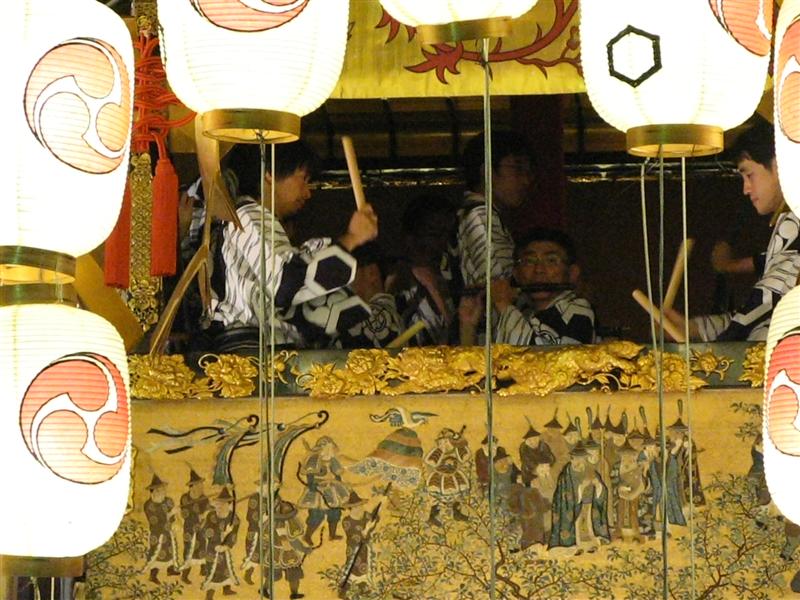

Another pleasure of the festival is viewing the floats. There are two kinds: yama and hoko. The hoko (the modern day descendants of the Heian era ritual halberds) will be hauled to Yasaka Shrine on the 17th in the grand parade known as Yamaboko Junko. They contain many fine art treasures and tapestries, reflective of the city’s rich mercantile history. John Dougill writes in his marvellous book Kyoto: A Cultural History of the festival’s strong links with commerce. During the 15th century the city’s merchants competed with each other to create the most beautiful and awe-inspiring floats. Here we see the “flourishing culture of the merchant-bankers who sponsored the festival. The mast-like halberds of the festival floats mirrored those of the ships that brought them profits, and they were draped with colourful fabrics imported from countries far away… It was the biggest of the city’s annual events, and today it still remains a potent symbol of Kyoto.”

John Dougill, Kyoto: A Cultural History, Oxford University Press, 2006.

Again, Yasunari Kawabata writes in the wonderful novel The Old Capital, of the “vigor” of old Kyoto’s merchant class.

Now that vigor remains in the procession floats, which are decorated with imported Chinese brocade and homespun, Gobelin tapestries, gold brocaded satin, damask, and embroidered cloth, examples of the splendor of the Momoyama Period, when beautiful articles reached Japan through foreign trade. The insides of the floats were also decorated with famous paintings. Tradition held that the pillarlike structures at the head of the floats had originally been masts on trading ships authorized by the shogun.

Yasunari Kawabata, The Old Capital,1962, Tuttle Publishing.

The floats are also filled with the musicians whose ubiquitous Gion bayashi music you will hear throughout the festival period.

During the festival homes and businesses along Shinmachi and Muromachi open up the front of their homes and shops to display publicly some of the beautiful antique treasures and folding screens in their possession. It’s funny to see people peering into people’s houses, especially when you can often see the owners inside, drinking festival sake and having a party with their friends, seemingly oblivious to the gawking onlookers!

Let’s take a peek too, shall we?

The stores were open with painted screens set out for decoration. There were early ukiyoe, Kano School and Yamato paintings and Sosatsu folding screens. Among the original ukiyoe there were some European screens, as well as foreigners depicted in the elegant Kyoto style that expressed the height of vitality of the Kyoto merchant class.

Yasunari Kawabata, The Old Capital,1962, Tuttle Publishing.

The three days leading up to the Yamaboko Junko parade on the 17th are the height of the festival. Yesterday, the 14th, is known as Yoiyoiyoiyama, tonight, the 15th, is Yoiyoiyama and tomorrow, the 16th, is Yoiyama. If you are in town, I’d recommend strolling down towards Shinmachi and Muromachi and enjoying the fun for yourself. Each night though the streets get a lot more crowded. It’s just my experience but I think the streets north of Shijo tend to be a little less crowded than the (jam-packed!) streets to the south where you will have to queue for a long period at the yatai or street stalls selling tasty festival food. After strolling through the crowds for a few hours (in geta!) your feet get a bit weary. It’s a good idea to find yourself somewhere to sit and have a quiet drink watching the festival viewers walk by. There are quite a few road side venues in the Sanjo/Karasuma area. Mewby and I, however, retreated to Joao for a quiet drink with friends. It’s not far from the main festival area and a haven after all those crowds! Here’s Mewby and Taisho, the genial master of Joao.

I will leave you with one last quote from The Old Capital, Yasunari Kawabata’s wonderful novel. There’s no book like it I think that captures the spirit of Kyoto, and the cycle of the seasons or its deep tradition. The Gion Festival naturally plays a big part in the novel, and indeed a pivotal scene takes place during the festival when the heroine Chieko meets… Ah no, I won’t tell you! You’ll just have to read it yourself! Here’s but a taster:

The sound of a Gion band drifted in from the town. The guest downstairs seemed to be a crepe dealer from somewhere near Nagahama in Omi. The sake had made several rounds, so their voices were rather loud. Snatches of the conversation reached Chieko where she lay at the rear of the second floor.

The guest stubbornly insisted that the reason the float procession now began at Shijo, went down the wide, very modern Kawaramachi, turned down Oike, and passed in front of City Hall was for the sake of tourism.

Previously the parade had followed the narrow streets typical of Kyoto – streets so narrow in fact, that occasionally houses were damaged by the passing floats. Back then the procession had a grace to it. One could even receive a rice cake by reaching out from a second-story window as a float passed the house. When the floats turned off Shijo onto the narrow streets, one could not see the skirts of the floats, which was good.

Takichiro defended the new way, explaining that he thought it was splendid now to be able to the see the whole float easily on the wider streets.

Lying in the bedroom, even now Chieko could almost hear the sound of the floats’ great wooden wheels turning at a crossroad…

Yasunari Kawabata, The Old Capital,1962, Tuttle Publishing.

The Old Capital is available from amazon.com, amazon japan

and amazon.co.uk

John Dougill’s Kyoto: A Cultural History is available from amazon.com, amazon japan

and amazon.co.uk